Table of Contents

Ejnar Hertzsprung

Short facts

Ejnar Hertzsprung was born on the 8th of October 1873 in Frederiksborg, Denmark. He was married to Henriette Mariette Augustine Albertine Kapteyn who was the daughter of Jacobus Kapteyn. They married at the 16th of May 1913 in Groningen and were divorced on the 19th of January 1937 in the Hague. They had one daughter together, Rigel Hertzsprung.

For more information on Henriette Kapteyn: https://www.rug.nl/library/collections-locations/special-collections/collections/archives-inventories/kapteynhma-collectiebeschrijving

Life

Ejnar Hertzsprung (Danish pronunciation: [ɑjnɐ ˈhæɐ̯d̥sb̥ʁɔŋ]) was born on the 8th of October 1873 in Frederiksborg, Denmark. He was the son of Henriette Charlotte Frost and Severin Carel Ludwig Hertzsprung, who was the director of a life insurance company.

Although Hertzsprung is famous for his work in astronomy, he finished his studies in Chemistry in 1898 at the “Politechnische hogeschool” in Copenhagen.

After his studies, he went to Sint-Petersburg to become a chemical engineer but in 1901 he went to Leipzig in Germany to study photochemistry under Wilhem Ostwald. He also became an independent astronomer at the time. *wikipedia pagina https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ejnar_Hertzsprung

In the period 1911–1913, together with Henry Norris Russell, he developed the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram.

In 1913 he determined the distances to several Cepheid variable stars by statistical[clarification needed] parallax,[1] and was thus able to calibrate the relationship discovered by Henrietta Leavitt between Cepheid period and luminosity. In this determination he made a mistake, possibly a slip of the pen, putting the stars 10 times too close. He used this relationship to estimate the distance to the Small Magellanic Cloud.

From 1919 to 1946 Hertzsprung worked at Leiden Observatory in The Netherlands, from 1937 as director. Among his graduate students at Leiden was Gerard Kuiper. Perhaps his greatest contribution to astronomy was the development of a classification system for stars to divide them by spectral type, stage in their development, and luminosity. The so-called “Hertzsprung–Russell Diagram” has been used ever since as a classification system to explain stellar types and evolution.

He discovered two asteroids, one of which is the Amor asteroid 1627 Ivar.

His wife Henrietta (1881-1956) was a daughter of the Dutch astronomer Jacobus Kapteyn. Hertzsprung died in Roskilde in 1967.

Anecdotes and Stories

The most passionate person that was ever to walk the halls of the Observatory is without a doubt Hertzsprung. There are more famous stories about him than he has years to his life. Hertzsprung was so passionate about Astronomy that he is rumored to have observed on his wedding night.

Naturally the 25th wedding anniversary of Oosterhof’s in-laws was also not wanted to take place on a clear night. Hertzsprung therefore insisted in a friendly but urgent manner that the party be rescheduled.

Hertzsprung’s interest in Astronomy was unprecedented. There was once a calculations clerk who was sick for a long time, and then, newly recovered, walked along the Observatory road with Hertzsprung. “And how is it going with you?” asked Hertzsprung. “Well, all right, but I am better again,” answered the calculations clerk. “No, I didn’t mean that,” replied Hertzsprung. “I wanted to know how the results of your research were!”

Accuracy, precision, and correctness were always held in high regard by Hertzsprung. So were Hertzsprung and Oosterhof once in a train. Across from them sat another passenger that asked Hertzsprung what time it was. Hertzsprung said: “It is two o’clock, …, NOW,” to indicate that it was exactly two o’clock at that moment.

If Hertzsprung completed a calculation that was correct, he would hit the table with his ruler like a madman several times, yelling: “Yes, it's right, it's right!”

Hertzsprung also had two pots of ink on his desk. One of the two was the property of the Observatory while the other was Hertzsprung’s own. In the mornings, as Hertzsprung arrived in his office, he would empty the ink from his pen into his own pot, and fill the his pen with ink from the pot belonging to the Observatory. In this way, he could keep his work and his private life separate.

As the director of the Observatory, Hertzsprung made sure that there was a port window placed in his office. From there he could see at any moment of the day who was coming and going from the Observatory.

Hertzsprung liked involving other people in his work. He repeatedly asked himself what the outcome of his measurement would be if someone else were to read out the plate with a photographic image of a part of the sky. Over the years he had approximately 45 people read out the same plate. Each person had the freedom to leave out a stellar image that wasn't deemed good enough. One thing Hertzsprung did dictate: you had to write two numbers per square of the gridded paper, and you had to start writing in a particular square. In that time the astronomer Pragen, fled from Germany, came though Leiden on his way to the United States. He too got to read out 'the plate'. After working on it for half an hour Hertzsprung came to check on him, and remarked that his colleague missed the obligatory first square. Hertzsprung made the German colleague write it all over again to the right place.

Hertzsprung didn't only like involving people in his work, but also to pose problems to them. When they were eating with him in the co-operative kitchen for instance, not suspecting anything. He would then occasionally ask an employee what would happen if all the ice in Greenland were to melt. Most people would try to quickly calculate how many meters the sea level would rise, for instance. Hertzsprung also posed this question to A.J. Wesselink. He thought about it and answered: “Then, professor, it would be the first time that the Danish would have any use of Greenland”. This answer did not go over well with the Danish Hertzsprung.

Hastening himself with his frantic paces, Hertzsprung could also halt suddenly to fire questions at anyone he met. So it happened that he came running up the Observatory road one day, immediately noticing that chief instrument-maker Zunderman was pottering about in his garden. Whilst passing Zunderman he looked to the right and said, with surprise in his voice: “So, sir, took the day off?” Zunderman was speechless for a moment and then muttered: “But it's Sunday today, professor?” The only thing that mattered to Hertzsprung was Astronomy.

E. Hertzsprung

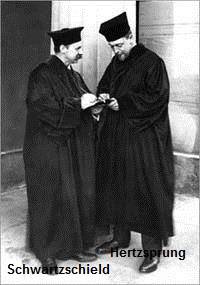

Ejnar Hertzsprung studied chemical engineering in Copenhagen, and became a specialist in photochemistry. He worked as a chemist in St. Petersburg before returning to Denmark to become an independent astronomer. In 1902 he was invited to Göttingen to work with Karl Schwarzschild (the guy from the Schwarzshield radius). He accompanied Schwarzschild to the Potsdam Astrophysical Observatory in 1909 where he stayed in Potsdam until moving to join De-Sitter in Leiden. From 1919-44 he worked at the Leiden Observatory in the Netherlands. During his last 9 years there he was its director. He then retired to Denmark but continued to work into his 90's. He died in 1967 at the age of 94.

He pioneered the studies of life and death of stars. He proved the existence of giant and dwarf stars as well as co-authored the Hertzsprung-Russel Diagram. In 1912, working independently, Ejnar Hertzsprung from Denmark and Henry Norris Russell from the United States of America made the discovery that the luminosity of a star is related to its surface temperature. His work combined with that of Russell, resulted in the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram of types of stars. Hertzsprung also made many other scientific discoveries. In 1913 he developed the method of distance determination using Cepheid variables.

It is surprising to note that most of Hertzsprung's work was done as desk work. He did not do the field research that many astronomers did but rather he specifically worked with information from other scientists looking for data that had previously been overlooked .

Hertzsprung was a complete workaholic, devoted to astronomy, showing little interest in his environment. His marriage to Kapteyns daughter Henriëtte was a failure from the beginning. Hertzsprung was not very interested in female company. The relation to his daughter, called Rigel (!), was however intimate during whole his life.

By his monomanic interest Hertzsprung was not popular with his personnel. In the WW-II he kept his post. Being a scientist, and not too well treated here as a Dane, he did not want to be involved. The observatory provided hiding places and printing facilities for the underground. Moreover the Astronomen Club kept meeting here with good attendance. E,.g. v.d. Hulst’s lecture on the 21 cm line was delivered here early 1944.

Hertzsprung retired shortly after the war, already long past his retirement age of 70 year. During his stay in Leyden he lived in the very first house (East) of the main building. He never moved in the directors’ house. Oort moved in there after de Sitter died.

Obituari Hertzsprung

history of Hertzsprung period and personal history of Hertzsprung

other

Hertzsprung was the director of the Observatory during the time of the Second World War. Before he had obtained this position, he was a renowned chemist in Germany. The Germans did not expect such an Astronomy nut to mingle himself in war affairs. Therefore the Germans assumed that the Observatory did not concern itself with the resistance. The truth however was completely different. The newspaper 'Trouw' was printed at the Observatory. Weapons were stored there, which had previously been stored at the Kamerlingh Onnes Laboratory but were deemed unsafe there. And there was even someone in hiding at the Observatory.